by Benjamin Dye and Megan Vaughn (Smithsonian Leadership for Change)

Millions of visitors flock to natural history museums each year to visit public exhibits, but these spaces only scratch the surface of what natural history museums have to offer: behind the scenes, a wealth of valuable data can be found in meticulously curated and preserved collections spanning hundreds of cabinets and drawers––but when and how did all these items get there?

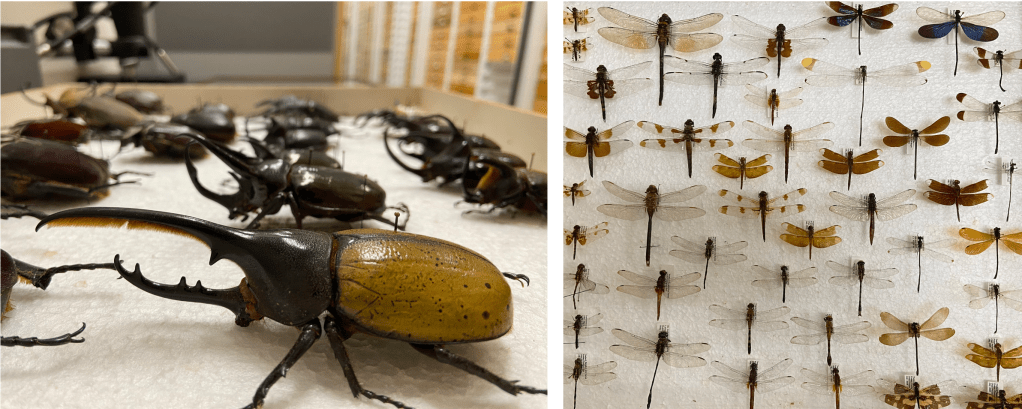

Museum specimens––snail shells, pinned insects, mammal skeletons, dinosaur fossils, bird nests and much more––are typically obtained through fieldwork, donations, and research. Many of these collection events date back hundreds of years. These invaluable repositories don’t just stay in near-perfect condition all on their own, however. Collections are maintained by curators and collections staff, who monitor and care for these items to ensure their vitality and future use to the scientific community. When utilized by researchers, teachers and government agencies, these collections can provide critical information that has been used to aid in policy making, public safety and health, epidemiology, and environmental research. As a permanent repository of snapshots through time, these collections can also help to document ecosystem change over millions of years.

During our VMNH orientation, we took a trip down to the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences to meet other collections staff, see other natural history collections, and visit public exhibits. We met Dr. Bryan Stuart, the Curator of Herpetology at NCSM. Dr. Stuart showed us the NCSM Ichthyology and Herpetology Collections, which house over 1 million specimens. We also visited the newly renovated molecular lab, where Dr. Stuart has been collecting genetic data for a project he is working on with Dr. Kuhn to identify new species of salamanders in Virginia and North Carolina. This collaboration exemplified how museums share resources and knowledge. Our visit underscored how collaborations enhance research capabilities, despite differences in collection sizes, benefiting scientific advancements and museum practices.

Natural history collections also lend insight to evolutionary processes such as speciation, extinction and adaptation. In our changing world, such studies allow us to understand how anthropogenic change can impact these processes. For examples, following the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, individuals noticed a higher prevalence of the Peppered Moth in its rare all-black form (Holmes et al., 2016). Dr. Henry Kettlewell used field experiments and museum specimen records to show increased predation of the common, non-melanic peppered moth and to test the correlation between melanism and industrialization across Britain. Kettlewell’s work paved the way for others to use collections to study the genetics responsible for melanism. Today, these peppered moths can still be examined in natural history collections to revisit these questions with continuously advancing scientific technologies.

Museums play a vital role in storing and managing collections through meticulous sampling and comprehensive data recording of specimen identity, location, and collection date. These curated collections are invaluable resources for scientific research, providing essential access to specimens that are otherwise difficult or expensive to obtain. While natural history museums attract millions of visitors annually, the true significance lies in the carefully preserved collections that underpin extensive research efforts. Before beginning our internship at the VMNH, we were unaware of the wide array of purposes collections served, but it has been an invigorating experience delving into this world of collections that often lies behind the scenes of the public museum experience.

Before beginning our internship at the VMNH, we were unaware of the wide array of purposes collections served, but it has been an invigorating experience delving into this world of collections that often lies behind the scenes of the public museum experience.

In conclusion, natural history collections play an indispensable role in advancing scientific knowledge and understanding. By meticulously storing and managing specimens, museums create a comprehensive library of data that spans centuries, offering invaluable resources to researchers. Natural history collections not only help us learn from the past but also guide future research and policy-making, ensuring that we can adapt to and mitigate the effects of our ever-changing world.