by Benjamin Dye and Megan Vaughn (Smithsonian Leadership for Change)

Natural history museums are filled with numerous specimens (Over 1.1 billion objects between the 73 largest natural history museums in the world!) that can be used by scientists around the globe for research—but what makes a specimen “usable”? The record of each specimen must be digitized! But what is digitization? Museum digitization refers to the process of creating digital representations or records of objects, artifacts, documents, and other items that are housed within museums. Museum specimen digitization involves transitioning information traditionally recorded on paper into digital formats stored in global repositories. Museum digitization aims to leverage technology to preserve specimens, improve accessibility to collections, and facilitate research and education in the digital age.

Specimen digitization offers numerous benefits including enhanced efficiency, improved accessibility, and streamlined collaboration. By bridging historical specimens with modern tools, new and previously unknown data is unearthed. This transformation of specimen data into readily accessible digital formats fosters broader utilization across various fields of study. Consequently, there has been an uptick in scientific research referencing museum collections, facilitated by this increased accessibility. Moreover, digitization serves as a safeguard for physical specimens, as digital data can be utilized instead, thereby aiding in their preservation.

Examples of modern digitization projects include the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, and iDigBio (Integrated Digitized Biocollections). These databases provide vast amounts of biological information from all over the world, including pictures, audio clips, and 3D models. One major digitization project was the oVert project. The oVert project consisted of the efforts of 18 museums from 2017 to 2023, with the goal to digitize the CT scans of over 13,000 vertebrate specimens preserved in fluid.

Museum digitization aims to leverage technology to preserve specimens, improve accessibility to collections, and facilitate research and education in the digital age.

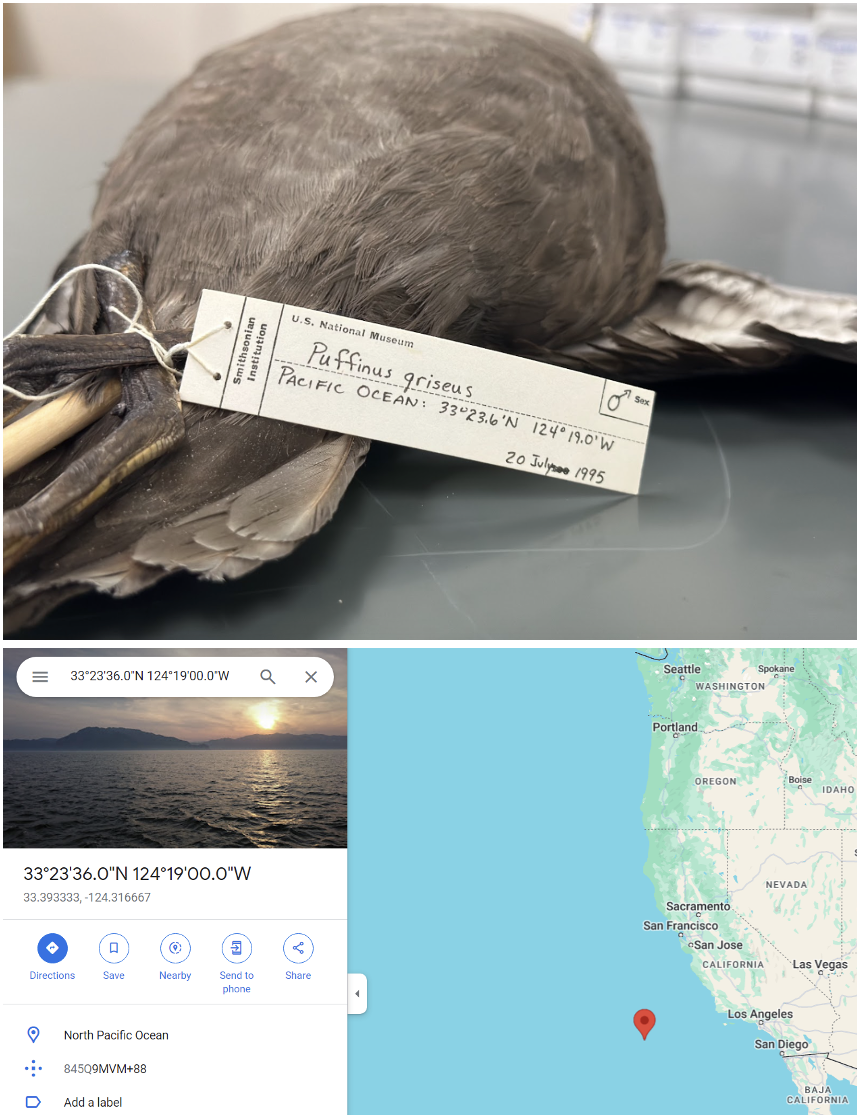

During our internship, we gained firsthand insights into the complexities and importance of specimen digitization. We discovered that locality and date data are crucial for determining the research quality of specimens—a factor that can significantly impact their scientific value. One challenge we faced in this process was a standard for recording data. Some tags contained minimal details like state and county, while others included extensive geographical coordinates.

For instance, one Sooty Shearwater (Puffinus griseus) we came across was collected in 1995. The record data for this specimen had coordinates pointing to the Pacific Ocean (see image on left)! We also came across an interesting Common Yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas) that was collected from Anolostan Island in the Potomac in 1883. After searching, we could not find a current record of this island, because it has been renamed to Roosevelt Island! Those tasked with digitization need to be experienced in history as well because the political boundaries of our world are ever-changing.

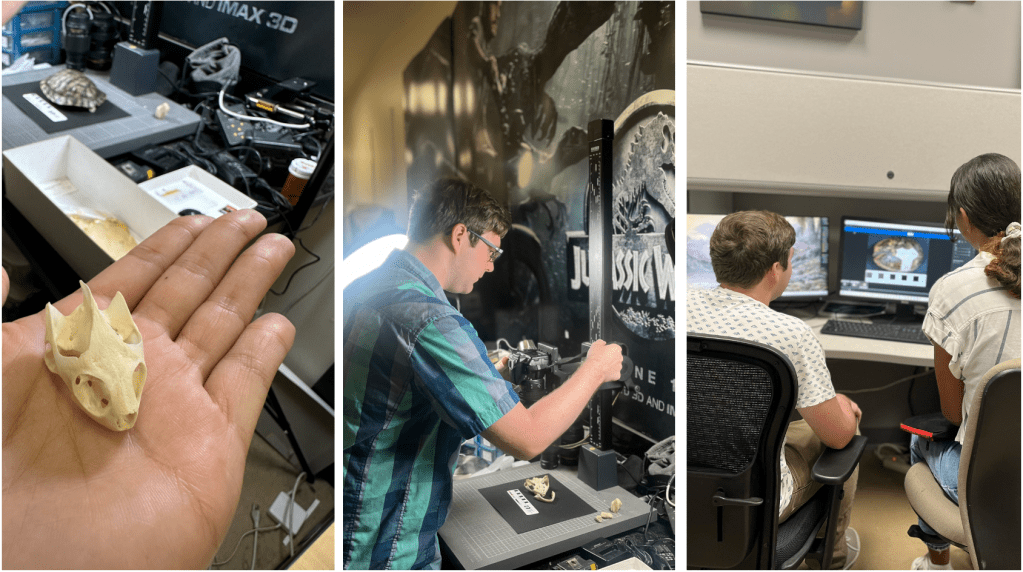

Our contributions to the digitization efforts were twofold: Firstly, we meticulously photographed the shells and skulls of various turtle species, and the bodies and skulls of several snakes, aiming to create visual aids for accurate species identification. This required us to develop photography skills including changing the focus, aperture, and shutter speed. We also needed to learn how to edit photos in software like Adobe Lightroom. Once our photos were edited, they were attached to digital records so scientists from all over the globe can examine and study the specimens. Secondly, we assisted in transferring data from a donated bird collection to the VMNH database. When working on the bird collection, it took almost 15 hours to digitize 293 bird specimens. The raw time commitment is a big challenge museums face when digitizing information, but this process is essential as it assigns VMNH numbers to specimens, enabling their use in future research endeavors.

Example of our digitization process from left to right: (1) Example of turtle skull to be digitized, (2) Ben photographing a Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) skull, and (3) Ben and Megan editing a photo of a Mud Turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum) for their specimen photography project.

Our experience with digitization has been immensely rewarding, providing us with a deeper understanding of the inner workings of museum operations and the pivotal role of digitization in preserving and enhancing scientific knowledge.